THE GOLDEN ERA OF AVIATION

…was the period of aviation between the great wars. It was defined by the change in how planes were constructed, flown and the distances they could travel. Prior to 1918, planes were mostly wooden biplanes covered in fabric making them slow and cumbersome. With new tooling and innovation, the biplane was soon replaced with the sleek streamlined metal monoplane.

Engines became lightweight, increasing the planes’ power and performance, allowing it to attain greater distances in shorter periods of time.

As civil aviation entered this golden age, many high risk and daring expeditions were undertaken. These included transatlantic flights, attempts in circumnavigating the globe, crossing Europe and the first air races. Many commercial airlines were started, offering luxury long distance flights to foreign lands that previously had taken weeks to reach via boat or rail.

If the 1560s had been the maritime golden era, the 1930s were the aviation golden era with pilots reaching for the skies and pushing boundaries.

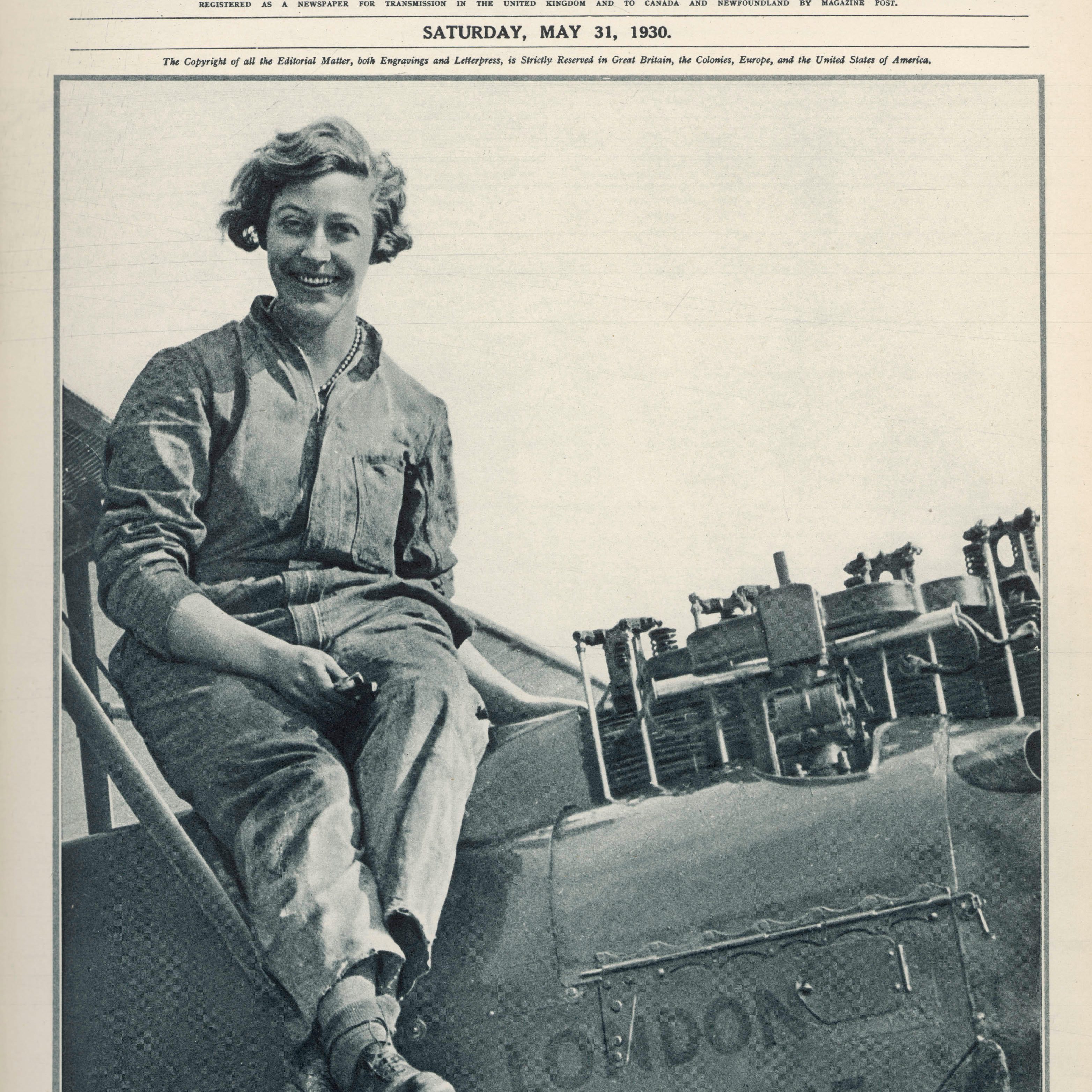

JOHNNIE

Amy Johnson was a leading pioneer in very male dominated world. This was soon to change, as herself, Amelia Earhart, Bessie Coleman, Harriet Quimby led some of the most ground-breaking achievements in aviation history. For all these ladies (as with many adventurers) a huge amount of risk had to be taken to capture the rewards.

It was said "the younger generation of women aviators personify the godlike quality of courage".

Beneath Amy’s glamorous appearance there was backbone of steel. She liked being called ‘Johnnie’ by her friends and was determined to do the impossible and rewrite the rule book. In fact, her flying success depended on her hard-won engineering expertise; knowing how to patch up and repair her planes when things went wrong. She was the first woman to gain a British Air Ministry ground engineer's licence, and from 1935 to 1937, she served as president of the Women's Engineering Society.

She challenged how women were portrayed and was convinced that women also had the vital qualities needed in aeronautical engineering - ‘patience, skill, delicate fingers and a fertile mind’. There was no reason that they could not succeed, whether it was in the design department, workshops or repair shops.

MAKING OF A LEGEND

In 1930 Amy flew a single engine De Havilland Gipsy Moth called Jason from Croydon Airport to Darwin in Australia. She flew alone and completed the epic journey within 19 days, covering 11,000 miles without any assistance. Prior to this feat the furthest she had flown was 186 miles from London to Hull.

Her route took her over inhospitable terrain and extreme landscapes, sometimes forcing her to fly for over eight hours at a time until she could land safely. When flying over Iraq, a sandstorm forced her to land in the desert, but this did not stop her setting a record in reaching India within 6 days. She reached Burma (Myanmar) two days later during the monsoon season, and unfortunately Jason was damaged during the landing. This set-back unfortunately cost her the record to Australia, but the world was stunned, nevertheless. She quickly became famous and was rewarded a CBE by King George.

When asked on the radio why she flew all the way to Australia, she replied, "My flight was carried out for two reasons: because I wished to carve a career in aviation for myself, and because of my innate love of adventure."

QUEEN OF THE SKIES

Being a national treasure didn’t slow her down and in July/August 1931 she set another record, this time for the fastest flight from London to Japan. The plane she was flying was a de Havilland Puss Moth.

In July 1933, Amy flew with Jim Mollison, her husband, from Pendine Sands in South Wales to Brooklyn, New York. They flew a de Havilland DH.84 Dragon called ‘Seafarer’ with the aim of completing a non-stop flight. Running low on fuel and flying in the dark they decided to land short of New York at Stratford, Connecticut. With no landing lights to aid them, they missed the runway crash landing in a drainage ditch. Both were thrown from the aircraft but survived. They were feted by New York and given a ticker tape parade.

In 1934 the pair set a new record from Britain to India in de Havilland DH.88 Comet called ‘Black Magic’.

In 1936 Amy made her last record-breaking flight from Britain to South Africa and back in 7 days, 23 hours and 46 minutes. When she landed she was swarmed by the waiting press and adoring public who had listened to her epic flight via the radio.

THE LAST FLIGHT

After the outbreak of the Second World War, Amy Johnson joined the war effort as a pilot with the Air Transport Auxiliary, moving Royal Air Force planes between airfields across the UK.

On 5th January 1941 Johnson departed from Blackpool en-route to RAF Kidlington in Oxfordshire. The flight should have been 90 minutes but 4 hours later she crashed into the Thames Estuary off Kent, some 100 miles off course in freezing winter conditions.

Johnson’s parachute was seen coming down by the crew of HMS Haslemere, which set out to rescue her. She was seen alive and shouting for help in the water but was unable to reach the lines thrown to her before disappearing beneath the ship. Johnson’s body was never found.

Speculation about her death has continued over the decades. There was a rumour of two bodies in the water, giving rise to the theory that she was on a secret mission having flown out to France and back. It was also thought that she had been shot down by friendly fire having not acknowledged call signals given to her.

HER LEGACY

Since her death, the story of Amy Johnson has been retold and reinterpreted in films, songs and fictional accounts, and her life has been commemorated in many different ways, from the erection of statues to the naming of buildings and aircraft.

Johnson was one of the most celebrated personalities of the decade and became a leading role model for women’s equality across the globe. She was a beacon to generations of girls who dreamed of breaking free from domestic drudgery for a life of romance and adventure.

A true pioneer, she overcame her fears, and made her mark in a world dominated by men and lived her own words ‘Believe nothing to be impossible.’