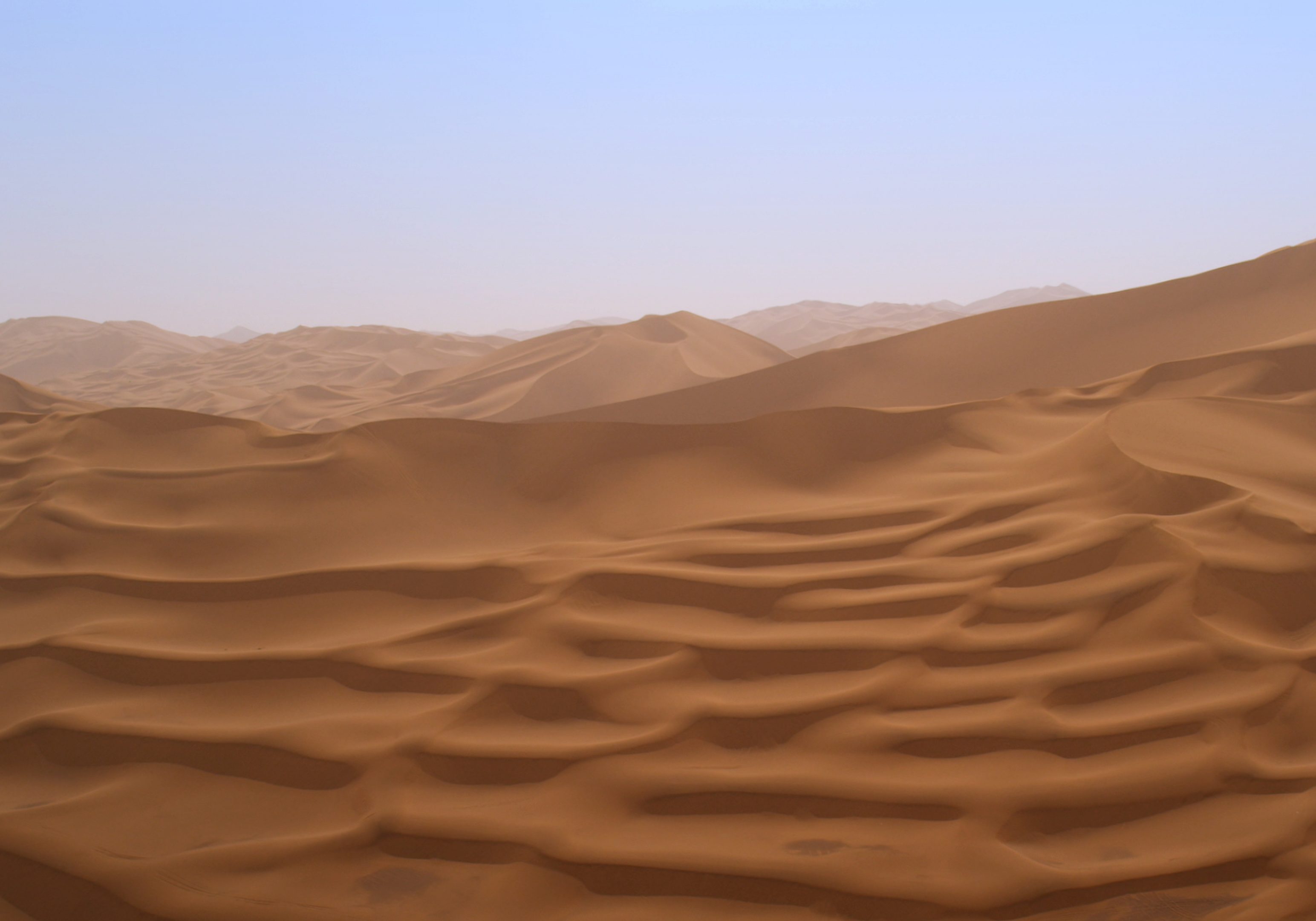

It is hard to describe the lure of the desert, most people see endless sand, dunes and oppressive heat. Blazing sun gives way to bitter cold and dark nights with a backdrop of stars glittering like jewels in the sky. With its raw beauty, hidden treasures of lost and bygone eras it is easy to see how stories have been created romancing this landscape. This is turn has attracted explorers, romantics, adventurers and escapees to its edges for a millennia.

The Taklamakan Desert was part of the fabled ‘Silk Road’ which connected the Far East with Europe between 114 BC and 1800 AD. It’s translated name is the ‘Desert of Death.’

THE TAKLAMAKAN DESERT

The Taklamakan Desert has an area of 337,000 km2 (130,000 sq. miles), located to the west of the Gobi Desert in China. It is the world's second largest shifting sand desert where 85% is made up of shifting sand dunes. Because it lies in the rain shadow of the Himalayas, Taklamakan has a cold climate with temperatures recorded in wintertime, sometimes below −20 °C, while in summer they can rise to 40 °C.

Sea Routes by the 15th and 16th centuries, had replaced the old overland routes to East Asia. With trade no longer flowing overland this quickly led to the demise of the oasis towns that surrounded the Taklamakan desert, which in turn became a symbol of mystery and intrigue for Europeans. The desert was said to be haunted by demons and spirits, with lost cities and gold to be found beneath its sands.

The first European to make a notable study of the region was the Swedish explorer Sven Anders Hedin, who returned from his first trek (1893–98) with artifacts of a completely forgotten Buddhist civilization.

Sir Aurel Stein excavated several towns in 1900 which had been buried over time by the desert sands. His discovered a large amount of Buddhist art adding to the lure of this forgotten desert. This expedition set off an international race to rob the Taklamakan of its ancient treasures, which ceased only in the mid-1920s when the Chinese forbade any further exploration.

No one had traversed this desert until Charles Blackmore decided to undertake this challenge in 1993.

THE LURE OF THE DESERT

In 1985 Charles followed the footsteps of Lawrence of Arabia, crossing some of the most dangerous wildernesses, through 800 miles of the Jordanian and Saudi desert on camel. This expedition ignited his passion for the desert, with its open spaces always acting as a ‘Siren’ trying to beckon and lure him back.

Whilst escaping from the confinements of a lecture, Charles found himself immersed in ‘The Times Atlas of the World’ looking for a new challenge and found himself staring at the ‘Taklamakan Desert.’ Some quick research and learning that this was one of the harshest deserts on earth, he found himself beginning to formulate a plan to navigate to navigate across its 1288 km length (800 miles).

After 5 years of planning, in 1993 he found himself leading a joint Anglo – Chinese expedition, with a caravan of 30 camels, traversing the unchartered Taklamakan desert from west to east.

THE EXPEDITION

The expedition was to be an Anglo – Chinese expedition supported by a team of Uyghurs who would manage the camel train. Charles describes in detail the challenges between the cultures and how they operated in his book.

Due to the conditions they were to face it had been estimated that each person would require at least 5 litres a day, whilst camels would require 13.3 litres per day. The team knew they would have to dig at points in hope of finding water but there was a rub; no one knew where to find the water as no one had been through this part of the desert.

Whilst the expedition was equipped with GPS navigating equipment, HF radios, satellite radios and Pinz Gauer vehicles for the support team, it was to be the camels, water, guts, grit and determination that would seem them through.

CROSSING THE TAKLAMAKAN

On 24th September having only been insitu for 5 days and not fully acclimatised (1,500m above sea level) the team entered the desert. Within days of setting out several team members started to suffer dysentery which caused their bodies to weaken under the relenting sun and climbing the continual sand dunes. The cause was a frying pan that the team used, which had subsequently unknowingly to them then been used to feed camels by their handlers.

The first leg was a gruelling 220 miles to Mazar Tagh, an old fort built in 1 AD. Despite their weakened states the team continued to navigate their way across the desert to Mazar Tagh causing them to wonder if they would escape the clutches of the desert.

Each evening a radio update would be provided back to base camp with two common topics, heat and the conditions. The English response would be ‘Not too bad, about 37c.’ The Chinese response would be ‘It’s awful, really, really bad. We are all dying of thirst.’

Having reached Mazar Tagh the team resupplied and rested under the shade of the old hill fort before starting the second leg was towards Tongguzbasti, a small settlement 110 miles north of the southern silk road. During this second leg the support team nearly lost one of the support vehicles as it sank into mud whilst following the riverbed towards the rendezvous (RV) point. The team reached Tongguzbasti on 14th October, which meant that they had come 300 miles in three weeks.

They still had 500 miles to cross, each day being a struggle against the sand, the constant thirst and never-ending sand dunes, though the temperature was soon to become a factor with temperatures plummeting below zero.

Charles recounts the moment they finally exited the desert at Luobuzhuang as an anti-climax. The skies were overcast and grey, with sand quickly giving way to a flat pebbled terrain with the end point marked in the distance by a flying a Union Jack. It had taken fifty-nine days and the desert had been finally conquered.

Against all odds the team had pulled it off.

All images by Keith Sutter who was the offical photographer of the expedition.

TREASURES OF THE DESERT

All images by Keith Sutter who was the offical photographer of the expedition.

Throughout the crossing there were times when the team found unexpected treasures. These came in many forms, unexpected riverbeds, lone trees, small copses of trees, dried lake basins and the all-important water sources. At the Mazar Tagh fort many of the team unearthed relics that should have been in a museum, these in turn were passed across to the Chinese at the end of expedition.

The most spectacular finding was some pottery which then led to the discovery of three houses still with fencing and pottery lying around them having been left undiscovered for seventeen centuries. The desert still retains many secrets yet to be discovered.

The full account of the crossing can be read in 'Conquering the desert of death' by Charles Blackmore.

I wish to thank Keith Sutter for sharing his images of this incredible expedition with us and allowing us to use them.